In the realm of psychology, classical conditioning stands as a testament to the profound influence our environment can have on our behavior. Pioneered by Ivan Pavlov in the early 20th century, this fundamental learning principle has left an indelible mark on our understanding of how associations are formed and maintained.

Image: animalia-life.club

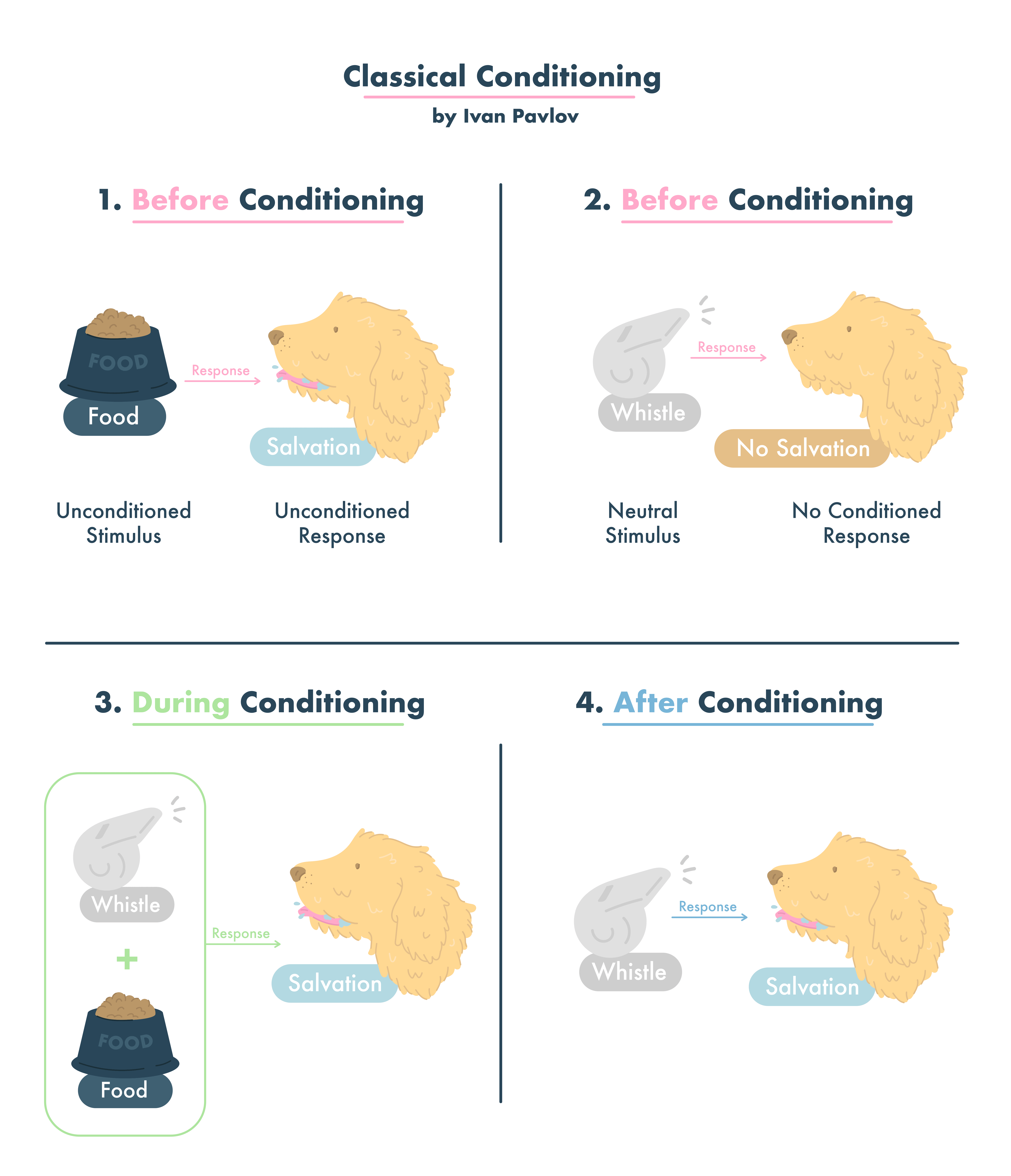

At its core, classical conditioning is a process whereby a neutral stimulus comes to elicit a particular response after repeated pairing with a naturally occurring stimulus. To illustrate this concept, let’s consider Pavlov’s groundbreaking experiment with dogs. In his experiment, Pavlov paired the sound of a bell (a neutral stimulus) with the presentation of food (an unconditioned stimulus), which naturally elicited the physiological response of salivation in dogs (the unconditioned response). Through repeated pairings, the initially neutral bell eventually became a conditioned stimulus, triggering the response of salivation (the conditioned response) in the absence of food.

This phenomenon illustrates the essence of classical conditioning: the ability of the brain to link two seemingly unrelated stimuli, subsequently leading to a learned association. In the above example, the dog’s initial reaction to the bell was one of indifference. However, after repeated pairings with the presentation of food, the mere sound of the bell became capable of prompting salivation, even in the absence of the food itself. This process, known as stimulus substitution, highlights the profound ability of our brains to form and strengthen associations through experience.

Beyond Pavlov’s seminal work with dogs, classical conditioning has been studied and applied across a wide range of species, from rodents to primates and humans, solidifying its relevance and universality in the animal kingdom. Moreover, it has found practical applications in various fields such as psychology, behavioral therapy, and marketing. Let’s explore some compelling examples to elucidate the power and far-reaching impact of classical conditioning:

Phobias, the irrational and often intense fear of specific objects or situations, often stem from classical conditioning. In a classic case, a person who has had a traumatic experience involving, let’s say, a spider, may develop an associative fear of spiders. The mere sight or thought of a spider (the conditioned stimulus) triggers an exaggerated fear response (the conditioned response), even in the absence of any real danger. This learned fear can have a profound impact on an individual’s life, causing avoidance behaviors and distress.

In a bid to alleviate these irrational fears, behavior therapists utilize a technique known as systematic desensitization, a form of counterconditioning grounded in the principles of classical conditioning. In this approach, the therapist guides the individual through gradually increasing levels of exposure to the feared stimulus while simultaneously pairing it with relaxation techniques. Over time, this systematic exposure weakens the link between the feared stimulus and the fear response, allowing the individual to navigate their previously anxiety-provoking situation with newfound ease and confidence.

Classical conditioning finds its application in the realm of marketing and advertising as well. Companies often leverage classical conditioning to evoke positive emotional responses towards their products or brands. Through repeated pairings with pleasurable stimuli or positive experiences, marketers aim to create a lasting association between their products and feelings of desire, happiness, or nostalgia. This subtle yet powerful influence can sway consumer behavior, driving brand loyalty and boosting sales.

While classical conditioning holds immense potential for shaping behavior, it is not without limitations. One being extinction, the gradual decline or disappearance of a conditioned response when the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented in the absence of the unconditioned stimulus. This phenomenon is often observed in animals with extensively conditioned behaviors. The gradual weakening of the association between the two stimuli leads to the conditioned response gradually diminishing and eventually ceasing altogether.

In conjunction with extinction, another factor that can influence the strength and persistence of classical conditioning is stimulus generalization. This refers to the tendency for a conditioned response to be elicited by similar stimuli, even when they are not identical to the original conditioned stimulus. The broader the generalization gradient (the range of stimuli that trigger the response), the stronger the conditioning.

In summary, classical conditioning stands as a formidable force in shaping behavior through learned associations, offering a comprehensive lens for understanding a vast array of psychological phenomena. Its far-reaching applications, coupled with its foundational role in psychology and behaviorism, cement its enduring significance.

Image: pediaa.com

Which Of The Following Is An Example Of Classical Conditioning